{Mandatory preamble: As with all of my blog posts, the views espoused herein are mine alone and should be construed as neither shared nor endorsed by any organization with which I have an affiliation.}

{Mandatory preamble: As with all of my blog posts, the views espoused herein are mine alone and should be construed as neither shared nor endorsed by any organization with which I have an affiliation.}

{Courageous Spaces preamble: As the curtain began to close on 2020, I accepted two new roles at the University that would enable further concerted cultivation of an EDI agenda in my professional sphere of influence and work. I am delighted and honoured to serve on the Diversity Advisory Council for the Faculty of Medicine, as well as the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, both of which are chaired by selfless, passionate, and effective leaders. I am continuing to learn that the concept of ‘space’ figures prominently in the work of these committees, as with other initiatives seeking to advance the broad goal of humanity, respect, and freedom to flourish for all. Space that is owned. Space that is occupied. Space that is deserved. Space that may be taken or earned or relinquished. Space that should be decolonized. As we know, space is multidimensional, and absorbing a greater leadership role in EDI during a time of unprecedented and differential sorrow enabled me to reflect on how I’d like to bend it around me. A ‘safe space‘ is typically regarded as one that is free of judgment and aims to support and nurture the inhabitants. A ‘brave space‘, on the other hand, is one that aims to advance dialogue, potentially at the expense of comfort. In the former, the fragile are handled delicately; in the latter, they are challenged. I debated what to name this series, and thought long and hard about the concept of bravery. I decided that I fall short on being brave about this work. I promise you that I feel fear – of rejection, of judgment, of contempt, of backlash, of failure. Courage requires one to stand with that fear, and walk through it. This fight is worth it. Upon new dawn finally – and glacially – breaking over 2021, it seemed apt, then, to launch a ‘Courageous Spaces’ series of blog posts, the second of which – written awhile back and posted elsewhere – is elaborated and reposted below. I hope you find them courageous. I hope they inspire us all to think.}

{Trigger warning: violent dreams, trauma, bereavement, death}

This post is about projecting confidence. Or, rather, the gap that lives around doing so in the psyche of the average mid-career female academic. “Where do you get your confidence?” – a compliment in and of itself, my friends – is a question I’ve heard from trainees and peers a handful of times at least. In response, I will often invoke the force of lived experience. Many have heard me say before: “Your lived experience is your truth. And your truth is your power.” That’s the thing about lived experience. No amount of gaslighting or bullying can erase it. You own it. And, should you choose, you will live to tell it. That’s an uncomfortable reality for academic medicine, where comfort and status quo ask that you subdue your experience and revel in your box of shame. As Toni Morrison articulated in her famed speech, “A Humanist View“, delivered at Portland State University on May 30, 1975: “It’s important, therefore, to know who the real enemy is, and to know the function, the very serious function of racism, is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” The academic culture, in its brutal totality, wants you in that box. It needs you there. Having the confidence – unfurled, untethered, and rooted in your truth – that allows you to step out of the box, and burn it to the ground is hard. And annoying, marginalizing, and invisibilizing. After all, it’s the system that needs correcting, not you! But until the decision-makers get around to picking the low hanging fruit that is your immediate environment, make no mistake, your truth has the power to tie you down or set you free. As Erica C. Kaye, MD, wrote: “your stories are the fuel needed to drive change.” Sometimes we all just have to sleep a bit in order to wake up.

When human beings are asleep, our hindbrains are bathed in acetylcholine with reduced levels of serotonin and norepinephrine. This is an adaptive mechanism, inducing REM atonia, which prevents us from acting out our dreams and maiming our bed partners. Occasionally, the brain wakes up during REM but the body remains paralyzed, a phenomenon called aware sleep paralysis (ASP) where one is technically awake and conscious, but the body is fully paralyzed. I can attest that this is a very strange experience. Along with ASP and hypnogogic hallucinations (in my case, the experience of being consciously levitated from the bed whilst transitioning from wakefulness to sleep), I’ve lived through four decades of sleep walking, sleep talking, and extremely vivid dreams. None of this is bothersome to me, but it has affected how I interact with the world and exist in it.

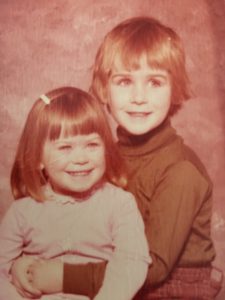

Unlike me, the person to whom I have been legally bound for approximately 87 years hits the pillow and does not wake until he feels the bone crushing agony of our son’s leaden calcanei torpedoing his thorax. My that child gets airborne in the morning! Permission to disabuse yourselves of the notion that a strident lecture on commotio cordis is any kind of deterrent to this behaviour. Suck it up, future parents! Kids land haaard. And occasionally on your most prized and breakable bits. Anyhow, back to my slumbering partner, whose nightly hibernation is so deep that he’s rarely sure if he’s even had a dream, let alone its contents. I, on the other hand, enter a completely different world during sleep. Elm Street is my middle name. I have bolted from the bed in the dead of night due to a lobster-sized tarantula either a. suspended above my head, or b. crawling towards my neck. I have engaged in weaponized mortal combat with all manner of villains; some battles were won by me plunging a sharp implement into my opponent’s flesh, while some were lost. I have slain with my bare hands. I have unleashed fury. I have locked eyes with evil. I have fortified remote and dilapidated cabins in the woods against raging lunatics, bloodthirsty bears, and packs of wolves. Huge wolves. Angry, activated, and cooperating wolves, not the cuddly, juvenile-rescue kind or even the skulking-shadows kind, whom I adore! I have of course fallen hundreds of feet into mossy crevasses. Like all vivid dreamers, I have shown up for tests at school either a. naked, or b. having not attended class all semester. I have been laughed off of stages in front of hundreds of people for belting out the raspiest, most terrible lyrics ever croaked out of a larynx. I have born witness to rabbits who, while being used in the name of science, have shed actual human tears, and cried actual human cries. I have even visited my dead twenty-year-old brother. That was……different; and pivotal. If nothing else had to that point, that dream revealed to me the box for the lie that it is.

It happened a few years ago now, set far in the past. As my teenaged self, I walked a corridor at some kind of institution – beige tiled floors and walls – toward a cafeteria with row upon row of tables. Before I entered the cafeteria, though, I saw my brother, sitting cross-legged in the alcove of a window, just as I remembered him, smoking a DuMaurier, which I found curious that the institution would allow. On his lanky, 6-ft-2-in frame was his usual outfit of a plaid flannel shirt, Levi’s, and royal blue high-top Converse. On his face were the wire-rimmed glasses correcting a refractive error brought on early almost certainly by a steady diet of hotdogs and microwave pizza, and smoking from the age of 15 onwards. When he saw me, he simply asked if our mom and dad knew that I had come to see him. In that instant, I could see the cafeteria filled with other young men, but there was not a single audible sound other than the voice of my brother. He stood up and dropped his butt, snuffing it out with the sole of his Converse. “You’d better go” he said to me, “it isn’t safe for you here”. I didn’t understand what he meant. I looked around; everything was calm, the silence enveloping my pounding heart. I felt fear; the hair on my neck stood on end, a chill snaked down my spine. But I listened to him and turned on my heel to walk away, registering disbelief. I rushed out, imploring myself to telephone my parents at once. All this time, all these years, my brother hadn’t been dead! He’d been……. incarcerated??? There he is in prison, waiting for us, over a dozen long hard years. Not buried in the ground, not six feet under. All this pain for nothing! I began to come out of the dream at this point, and was awash in relief. I have never felt such a weight lifted from my shoulders as I did in that moment, believing him to be alive. As immediate preludes to devastation tend to be, though, the moment was fleeting, and it didn’t take long in the cold grey light of early morning for reason to penetrate my thoughts. I remembered his body. Lying in a casket. Being lowered into the earth, on the most barren, slate, and frigid of days. I remembered the silk shirt and burgundy V-neck sweater – one of his best outfits – clashing horribly with the pallor of death. I remembered the sobbing, the search for clues, the desperation for answers, the exsanguination of grief. The suffocating denial.

The morning of this dream was the first time I had ever felt betrayed by slumber. Up until that point, even the most violent bloodbath dream had zero discernible impact. But not this one, no; this one recalibrated my centre of gravity and threw me off the tightrope. Alas, the opportunity to rise again only comes after a fall. Limited growth occurs when operating exclusively within one’s comfort zone. And so began that day several years ago. I try very hard not to be a bitch, which, depending on the scenario unfolding in my face, takes some effort. As every academic knows, it’s perpetual grant season, and on the very specific test of one’s immutable happy face that constitutes the results notification, I fail miserably on a repeated basis. This used to bother me – my inadequately veiled ambivalence, that is, not the actual failure to secure funding – and I would entertain the self-flagellation required to correct this intrinsic deficiency in my ability to care about such things. Get in the box! Feel the shame! Feel it!!! By translating my lived experience, my subconscious has mercifully taught me better, and to it, I must say thank you. Live your life. Don’t sweat the small stuff. Trust me, you’ll need room in your head for the big stuff. As someone much wiser than me once remarked, “this ain’t no dress rehearsal”. Now, without compunction, when a *particular demographic* calls me up to break the news that I almost made the cut, or with some ‘finessing’ and ‘grantsmanship’ I could improve my score by the necessary five hundredths of a point to qualify for funding, he’s gonna hear it in my voice that I just don’t give a crap. Step out of the box. And burn it to the ground.